The Cayuse War the Cayuse War Easy Drawings

The first major and ongoing conflict between Native groups and white resettlers in Oregon was a direct consequence of the murders by Cayuse tribesmen of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and eleven others at Waiiletpu, the Whitmans' mission near present-day Walla Walla, Washington, on November 29, 1847. Usually called the Cayuse War, the nearly two-year campaign waged by the Oregon Provisional Government in 1847–1848 and the Oregon territorial government in 1848–1850 was a mixture of military actions—there were few firefights—peace negotiations, and the pursuit of those who had killed the missionaries. A federal military detachment would not arrive in Oregon until May 1849.

By December 8, 1847, Governor George Abernethy had received news of the shocking events at Waiiletpu from Hudson's Bay Company Chief Factor James Douglas at Fort Vancouver. The Oregon Spectator carried a report of the killings the next day. For two weeks, the eighteen-member legislature wrangled over what actions to take. Following a secret meeting of the legislature, on December 25 legislators agreed to authorize the creation of a volunteer militia force of five hundred men to apprehend the Whitmans' killers and rescue the more than forty-five white captives being held by a few Cayuse.

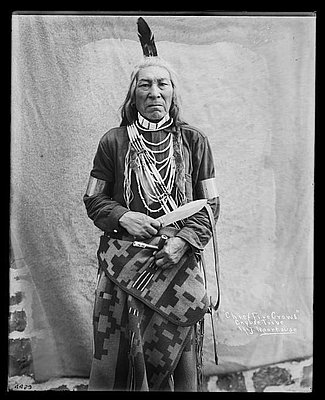

In Cayuse country, on the east side of the Cascades, Cayuse chiefs—including Camaspello, Five Crows, and Tilokaikt—agreed in council with Father Augustine Blanchet to participate in meetings to avoid a war. Also present were Catholic priests and Protestant missionaries in the Cayuse, Walla Walla, Umatilla, and Nez Perce homelands, who argued against vengeance by white authorities toward the tribes. Years later, Nez Perce headman Lawyer remembered that he and other Nez Perce were "perfectly bewildered" at the Waiiletpu killings and "knew not which way to turn."

Col. Cornelius Gilliam, a veteran of white-Indian wars east of the Mississippi, commanded the volunteer militia, aided by Maj. H. A. G. Lee and Lt. James Waters. The legislature appointed Joel Palmer as Commissary General and made him Superintendent of Indian Affairs, charging him with establishing peaceful relations with tribes in Oregon and with preventing further violence.

To avoid a region-wide war, the Provisional Government created a Peace Commission to prevent Nez Perce and Yakama forces from aiding the groups of Cayuse. Palmer was named commissioner, along with H. A. G. Lee, a former editor of Oregon Spectator who had some facility in the Sahaptin language of the Cayuse, and Robert Newell, Speaker of the House in the legislature and a former fur trapper whose wife was Nez Perce. Perrin Whitman, Marcus Whitman's teenage nephew who was fluent in Nimipuutímt, served the commission as interpreter.

Peter Skene Ogden, a trader for HBC, secured the captives' release by providing a ransom of trade goods, and they returned safely to Oregon City in early January. Several told their stories to the press, which increased public clamor for some measure of punishment. Reflecting popular opinion in Oregon Country, the Oregon Spectator demanded the vengeful pursuit of the Cayuse: "Oh, how terrible the retribution should be."

Also in January, the volunteer militia and the Peace Commissioners headed up the Columbia River to Waiiletpu. Governor Abernethy had told Palmer to conduct negotiations to end all violence, but he had instructed Colonel Gilliam to forcefully pursue and chastise the guilty Cayuse. The militia sought to engage the perceived enemy at every opportunity, and the entourage was slowed by two brief fights with Cayuse, the logistics of moving provisions and material, and the establishment of a fort at The Dalles.

The military column reached Waiiletpu on March 2, where the soldiers built a fortification. The peace commissioners arrived the next day. Three days later, the Nez Perce arrived, and the commissioners held a council with Nez Perce headmen the following day. Tuekakas, also known as Old Joseph, promised that the Nez Perce would not protect Whitman's slayers, and Palmer warned that there would be dire consequences if the Nez Perce aided hostile Cayuse. The commissioners were pleased with the council. "The war party of the Cayuses," Palmer reported to the Provisional Government, "are now so reduced in numbers that they are not likely to risk another engagement."

Palmer and Newell returned to the Willamette Valley, and Palmer resigned as Superintendent of Indians Affairs, in part because of a lack of federal support: "No appropriation having been made by the Legislature to meet the expenditures of this department, it necessarily requires heavy draws from the private means of the Superintendent. My pecuniary affairs is such that it will not admit this. I hope this will be considered a sufficient reason for taking this step." H. A. G. Lee took up the position and remained in eastern Oregon, while Gilliam and the militia pursued the Cayuse, even though reports confirmed that the guilty men had dispersed in several directions. He tried to engage any group he perceived as hostile, but the militia's only fight was with Palouse who had no connection to the Whitman killings. By late March, the American volunteers had run out of provisions and headed back to The Dalles. On the way, Gilliam died from an accidentally discharged rifle on March 24. Over the following five months, the militia had no luck forcing the Cayuse to give up the wanted men, and the Provisional Government ran out of appropriations and loans to sustain the volunteers in the field. The militia's military campaign ended in late summer 1848.

The punitive and even vengeful effort to chastise the Cayuse did not end, however, until Joseph Lane, governor of the newly created Oregon Territory, pursued a diplomatic solution. With the aid of the Hudson's Bay Company, he persuaded friendly Cayuse to offer five individuals for trial. By April 1850, Oregon officials had Chief Teloukaikt, Tomahas, Clokamas, Isaiachalakis, and Kiamasumkin in custody. The brief trial was held in late May in Oregon City before Judge O. C. Pratt and more than two hundred spectators. After conferring for just over an hour, the jury brought in a verdict of guilty for the five Cayuse, and the judge sentenced all to a public hanging on June 3, 1850. "Much doubt was felt as to the policy of hanging them," the New York Tribune reported, "but the popularity of doing so was undeniable." The Cayuse War ended as it had begun, with violence.

-

-

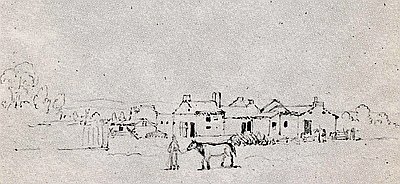

Whitman Mission, Paul Kane sketch of, ca. 1846.

Whitman Mission buildings at Waiilatpu, about 1846. From Thomas Vaugan, ed., Paul Kane, The Columbia Wanderer: Sketches, Paintings, and Comment, 1846-1847, OHS Press, 1971, p. 16.

-

-

-

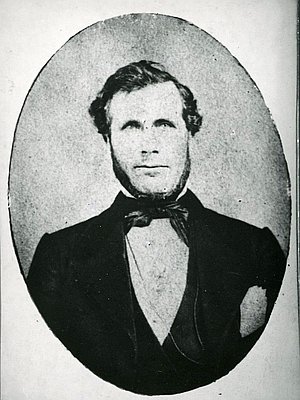

Joel Palmer, c.1860.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi362

-

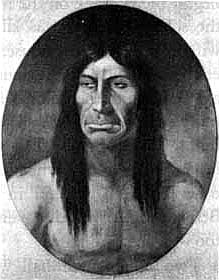

George Abernethy.

George Abernethy, Oregon's first and only provisional governor, 1845 to 1849. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb003864

-

James Douglas.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 39363, photo file 336

-

Peter Skene Ogden.

Peter Skene Ogden Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi707

-

Father Francois N. Blanchet.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library OrHi 61321 & bb004274

Related Entries

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Tate, Cassandra. Unsettled Ground: The Whitman Massacre and its Shifting Legacy in the American West. Seattle, Wash.: Sasquatch Books, 2020.

Victor, Frances Fuller. The Early Indian Wars of Oregon. Salem, Ore.: F.C. Baker, State Printer, 1894.

Josephy, Alvin M., Jr. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven, Conn.: Yale Univ. Press, 1965.

Karson, Jennifer. ed. As Days Go By: Our History, Our Land, and Our People: The Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla. Portland: Tamastslikt and Oregon Historical Society, 2006.

"Remarks of J. Palmer in Council with the Nes Perces, Walla Wallas and friendly Cayuses." Oregon Spectator, April 6, 1848.

"Report of the Peace Commissioners." Oregon Spectator, April 20, 1848.

Ruby, Robert, and John Brown. The Cayuse Indians: Imperial Tribesmen of Old Oregon. Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, Commemorative Edition, 2005.

Lansing, Ronald B. Juggernaut: The Whitman Massacre Trial, 1850. San Francisco, Calif.: Ninth Judicial Circuit Historical Society, 1995.

Stern, Theodore. Chiefs and Change in the Oregon Country: Indian Relations at fort Nez Perces. Vol. 2. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1996.

Source: https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/cayuse-indian-war-1847-1855/

0 Response to "The Cayuse War the Cayuse War Easy Drawings"

Post a Comment